By definition, a bad habit is a repetitive behaviour that is detrimental to a person’s physical or mental health. We all have bad habits: many people bite their lips or nails from time to time, pick at their pimples, or engage in emotional eating. They’re annoying, but they don’t consume your daily life.

The behaviour becomes a disorder, though, when it causes significant distress. When you realize that you can’t stop no matter how hard you try, how much it hurts, or how much time you waste on it, that’s when it becomes more than just a bad habit.

Body-Focused Repetitive Disorders

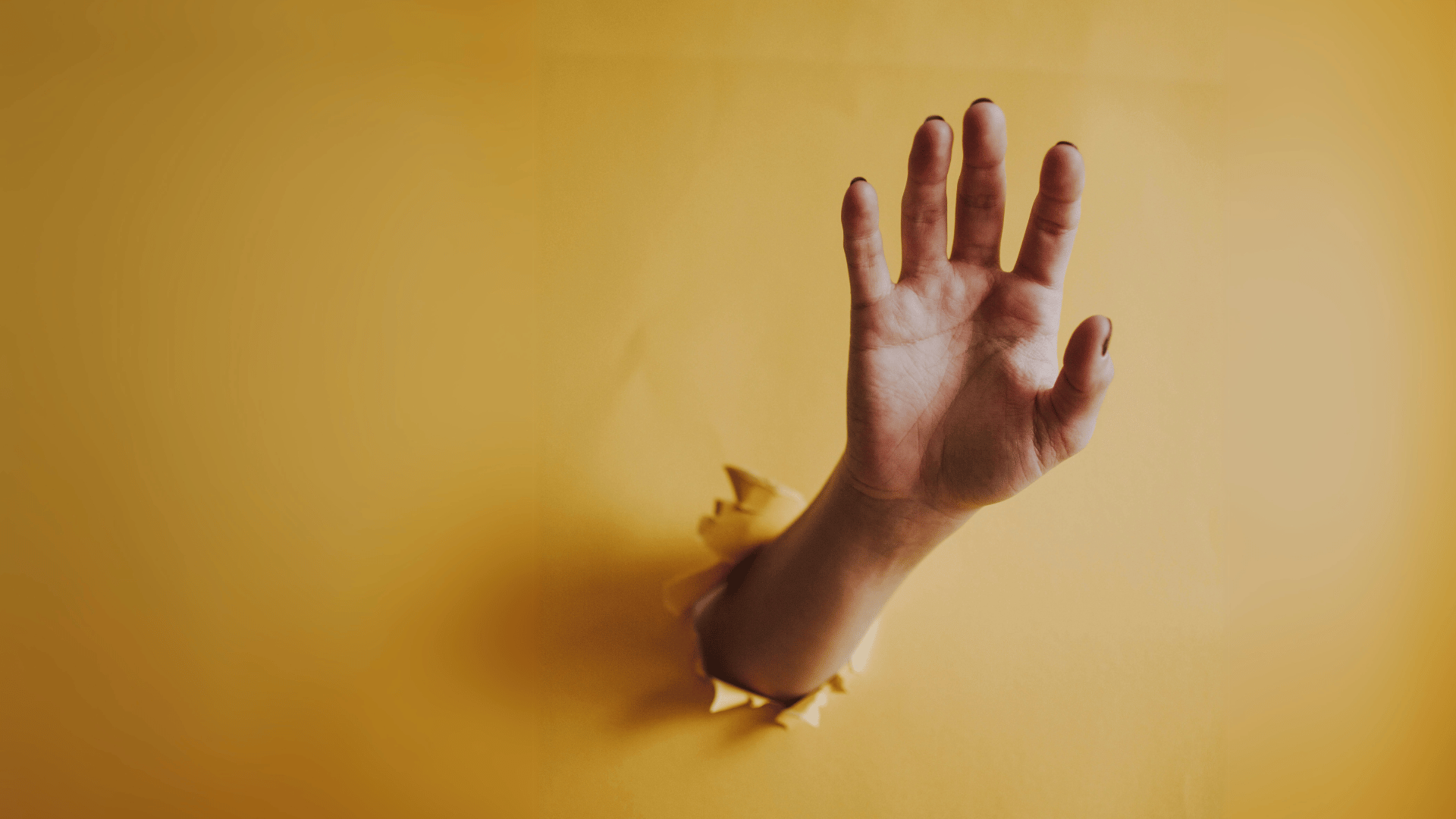

In recent years, I’ve become outspoken about what was once my deepest, darkest secret: my trichotillomania. Trichotillomania is the compulsion to pull out one’s own hair, often to the point of causing physical pain and creating bald spots.

While hair-pulling alone has caused me a lot of distress, trichotillomania is actually just one disorder in a broader category known as Body-Focused Repetitive Disorders (BFRDs). Other compulsions include skin picking, nail biting or ripping, cheek chewing, and lip biting.

Trichotillomania is the compulsion to pull out one’s own hair.

When I was younger, I used to dismiss these other behaviours as simply bad habits because I was so overwhelmed distressed by my hair pulling. But as I got older and became more desperately to control my trichotillomania, my compulsive needs shifted and my “bad habits” evolved. I began to be equally consumed and ashamed by the consequences of my skin-picking, nail-ripping and lip-biting.

Ritualistic behaviours

My hair pulling has always been ritualistic. I don’t just pull any hair; each one is carefully chosen by specific criteria. Once a hair is pulled, the ritual must be completed by feeling the root brush against my lip. If I’m dealing with a hair from my scalp, I must then rip it. When my rituals get interrupted, I feel a great deal of anxiety which compels me to start over from the beginning.

Rituals are a symptom of many mental disorders including OCD. They’re often another important red flag that lets you know a behaviour is more than a bad habit. My ritualistic behaviours are triggered by anxiety: but the more I picked my skin and ripped my nails, the more distressed I felt – and the more I was compelled to do it.

Lasting consequences

The consequences of living with BFRDs have often kept me up at night. Most of my life, I have had virtually no eyebrows and no eyelashes. I’m always thinking about my makeup and checking that my fake lashes haven’t peeled off. In attempts to leave my face alone, I sometimes resort to my scalp because bald spots are easier to hide there, but they can still be discovered if I’m not careful.

It physically hurts to pull at my hair and my nails, but it isn’t nearly as painful as the shame. I can’t count the number of times I’ve made up lies because I was embarrassed. When questioned about my limping, I’ve told people that I had broken my toe, when I’d actually completely pulled the nails off my pinky toes. I’ve lied about why I didn’t want to eat something acidic because it would burn my raw cheeks and lips.

BFRD symptoms may look like bad habits, but they’ve impacted me to the extent of dictating major life decisions, like like leaving home to travel indefinitely: when my hands are busy with driving, I don’t have time to pick at anything. My lashes look best at the end of a long road-trip.

Breaking the silence

The hardest part of living with BFRDs is how little is known about them, by both experts and the public. Before I learned more about it, I felt like a freak. Because BFRD symptoms can look like simple bad habits, people used to tell me to “just stop.” That made me feel awful, no matter how well-intentioned they were. Of course I wanted to stop. I would love to stop feeling grossed out by my behaviour, to stop needing makeup, and to stop limping.

As it’s often the case with mental illness, the key to breaking out of shame was to open up to the people around me. When I found the courage to tell my husband, my friends, even strangers about it, I was met with an incredible amount of support. Their understanding helped me accept myself: I still struggle with my “bad habits,” but I no longer let them send me spiralling into self-loathing.

The few experts on BFRDS estimate that this impacts 1 in 50 people, knowing there are likely many more hiding in the closet like I once did. Today, I try to share my story with as many people as I can, because it turns out life is a lot less lonely outside the shadows.

Need to get something off your chest?

Book a free phone or Skype vent session today.

-

Jade lives out of a backpack and can be found with either a camera, a pen, or a book in her hands at all times. She doesn’t believe in retirement and hopes to one day combine her BSc of Environment with her passion for storytelling. Follow Jade on Instagram: @jade.poetry

View all posts