Of all mental illnesses, eating disorders (EDs) have the highest mortality rate – and yet they’re still surrounded by countless myths and misconceptions.

As someone who struggles with an eating disorder, I find this extremely frustrating and alarming. These biases often prevent us from taking patients seriously, and sometimes encourage us to disregard the severity of their symptoms. It’s crucial for us to dispel these myths so we can understand EDs and be better equipped to help those who are affected by them.

“Eating disorders only affect women”

A common belief is that eating disorders only affect women. This is certainly not the case, and I can’t stress that enough. Eating disorders don’t discriminate: they can affect people of any gender, sex, age, ethnicity, race, or socioeconomic group.

The myth that only women have eating disorders isn’t only wrong: it’s dangerous, as it often makes it very hard for men to reach out for help. When they do seek help, popular biases can cause them to be underdiagnosed. It’s also important to note that EDs may manifest differently in men: for example, some can suffer from muscle dysmorphia, which leads them to engage in harmful behaviours, such as over exercising or using steroids.

“Eating disorder = anorexia”

When people think of EDs, they usually think of anorexia nervosa. Depictions of EDs often include a picture of an extremely thin girl standing in front of a mirror, terrified, staring into a figure at least twice her size.

When they hear “eating disorder,” most people tend to think of anorexia.

However, EDs are actually classified as a group of disorders: these include anorexia, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, and avoidant and restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), to name just a few. Orthorexia, to cite another, refers to an obsession with “healthy” eating; while it has already garnered a lot of attention from researchers, it isn’t officially included in the DSM.

Some eating disorders don’t have fixed diagnostic criteria. Some require treatments that can’t be reimbursed by insurances. Some are better known than others. But all of them are harmful and can have devastating consequences.

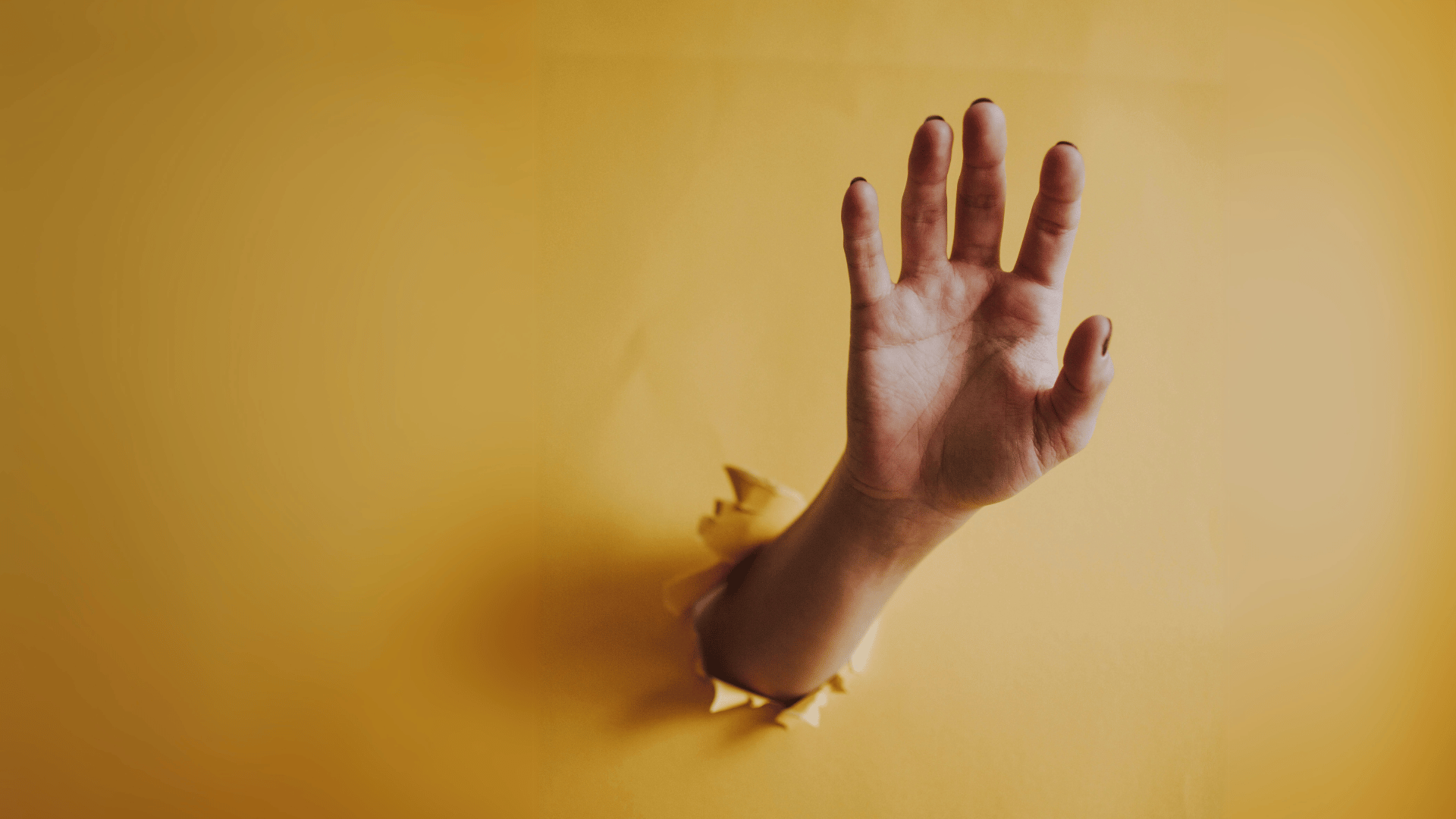

“Eating disorders are visible and obvious”

One of the most common myths about eating disorders is that patients have visible symptoms: they have to be extremely underweight, with visible collarbones, thigh gaps, and flat stomachs, among other traits. But the symptoms go much deeper than what we can see. In fact, many people who have an ED seem healthy—myself included.

When I was in the early stages of anorexia, I didn’t look sick. My parents thought my dietitian was crazy. “Márcia isn’t anorexic,” they said. “She eats. She’s slim, but she doesn’t have any bones popping out. Of course she doesn’t have anorexia.”

But my parents never saw me weighing myself five times a day, stepping on and off the scale four, five times every time, making sure the decimals didn’t change, keeping track of all those numbers in a small journal. They never saw me doing jumping jacks in the closet or taking out a hidden tape to measure different parts of my body. They never saw my smile whenever a ring would feel slightly looser on a finger, or the tears of despair whenever it’d feel tighter. They never noticed me wiping off with a napkin the excess of olive oil on my food.

Visible signs of EDs are just the tip of the iceberg. Just because someone doesn’t look like they have one doesn’t mean they’re not sick.

“People with eating disorders just lack willpower”

There seems to be a widespread belief that eating disorders are a choice, and that a patient’s inability to recover is merely due to a lack of effort. I often hear that if I don’t want to binge, I simply shouldn’t buy trigger food at the supermarket. Or that if I want to lose weight, I should simply work out more.

But recovering from an eating disorder is much more complex than that. EDs take a very heavy toll on patients’ physical and mental states: they’re emotionally draining, and they often bring a lot of shame. It doesn’t help a patient to hear that if they’re not getting better, it must be because they’re simply “not trying hard enough.”

When talking to or about someone with an ED, please take words like “just” and “simply” and throw them out the window. There is nothing simple about any eating disorder. The only way to understand eating disorders is to learn about them, and the best way to start is by listening to those who have experienced them firsthand.

For more information about EDs, please access the National Eating Disorder Information Center’s website.

Need to get something off your chest?

Book a free phone or Skype vent session today.

-

Márcia Ramos is from Rio de Janeiro and currently resides in Montreal. She gave up a career as a dietitian in order to pursue her dream of becoming a writer. Márcia still wishes to use her knowledge of nutrition and her firsthand experience with eating disorders to help others who struggle.

View all posts